Dispatch from Berlin

A nation with a very dark past provides us some hints for contending with our very dark present.

I was starting to be aware of the world around me roughly at the time the Berlin Wall was being erected. As an eight-year-old, I had no grasp of its significance in world affairs, but I knew from the somber tone of Walter Cronkite’s voice whenever he spoke of the wall that it wasn’t a good thing. The words “Checkpoint Charlie” carried an ominous message. I knew, as well, from the furrowed brows of my parents that there was something to be feared, vague though it might have been.

Some 28 years later, I was considerably more aware of the world when the Berlin Wall came down. It meant that the city could begin its reunification and that the specter of Communism that people of my generation had been raised to fear was beginning to dissolve, at least insofar as the Soviet Union was concerned.

So as I’ve walked around Berlin, I had moments of awareness that I was now freely walking around “behind the Berlin Wall” — that faraway place that had loomed so frighteningly in my imagination from such an early age. Little wisps of guilt or sedition or fear percolated to the surface, as if I were somehow still doing something forbidden.

Then my adult mind kicked in, and I began to see things in a slightly clearer perspective. I remembered perhaps the most important thing for Americans to remember these days — that oppressive regimes fall, usually under the weight of their own oppression.

Present day Berlin is full of reminders of Germany’s troubled history. But Berlin doesn’t bury those often horrific details of its past; instead, it acknowledges its failures as apart of its strategy for moving forward.

Take, for example, the memorial to the 500,000 Roma and Sinti murdered during the holocaust. The reflecting pool and the unflinching chronology on the walls that surround it remind us that, for current-day Germans, there’s no sugar-coating of those cruel pointless deaths:

A couple of blocks from the reflecting pool is the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, another somber public reminder of the holocaust. It’s hard to walk around and through that memorial without feeling the weight of the events that made such a memorial necessary:

Berlin has come through the atrocities of Nazism as well its inhumane division by the Soviets. But it hasn’t come out the other side by pretending those horrors didn’t exist. It has done so by acknowledging all of its history. In fact, it’s not just acknowledgement; it’s putting its failures on full display not only as a tribute to those who suffered grievous harm but also as an ongoing reminder of how easily a nation can slide into inhumane forms of government.

It’s hard to imagine an equivalent in the United States — public structures whose sole purpose is to remind us of our mistakes and failures.

Do we have a front-and-center memorial to the “settlers” genocide of indigenous peoples? No. We have public officials banning the honest teaching of the founding of the nation and our government continues to marginalize and impoverish Native Americans.

Is there any public admission of the many failures of our immigration system? Certainly not these days. The emphasis is on intentional marginalization, oppression, and exclusion of certain segments of the population — both citizens and non-citizens alike.

Has the nation fully come to terms with its centuries-long history of slavery? Hardly. While Washington, DC now has the National Museum of African American History and Culture, that museum is the result of decades of wrangling simply to be built. The GOP is doing everything in its power to make the nation’s history of slavery invisible — from tacit support of state and local book bans to the abolition of DEI programs throughout the federal government to the restoration of naming of military bases after Confederate “heroes.”

Berlin provides a glimmer of hope that a culture with a dark history can reconcile its past to create a viable way forward. A culture that is perpetually telling itself that it is “the greatest” doesn’t leave itself much room for improvement. But one that looks honestly at its own past and understands that it can and must do better positions itself to prevail in the years ahead.

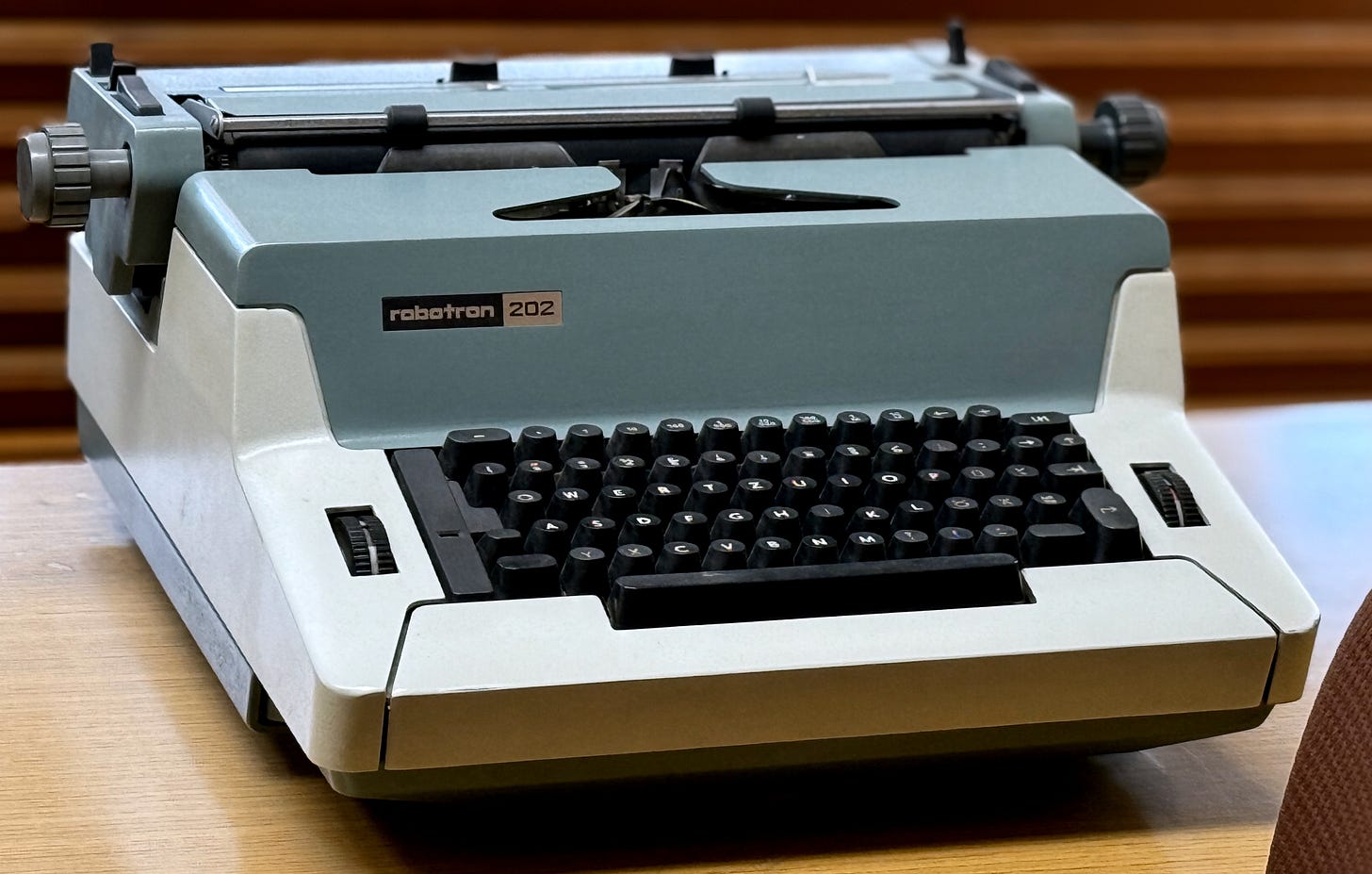

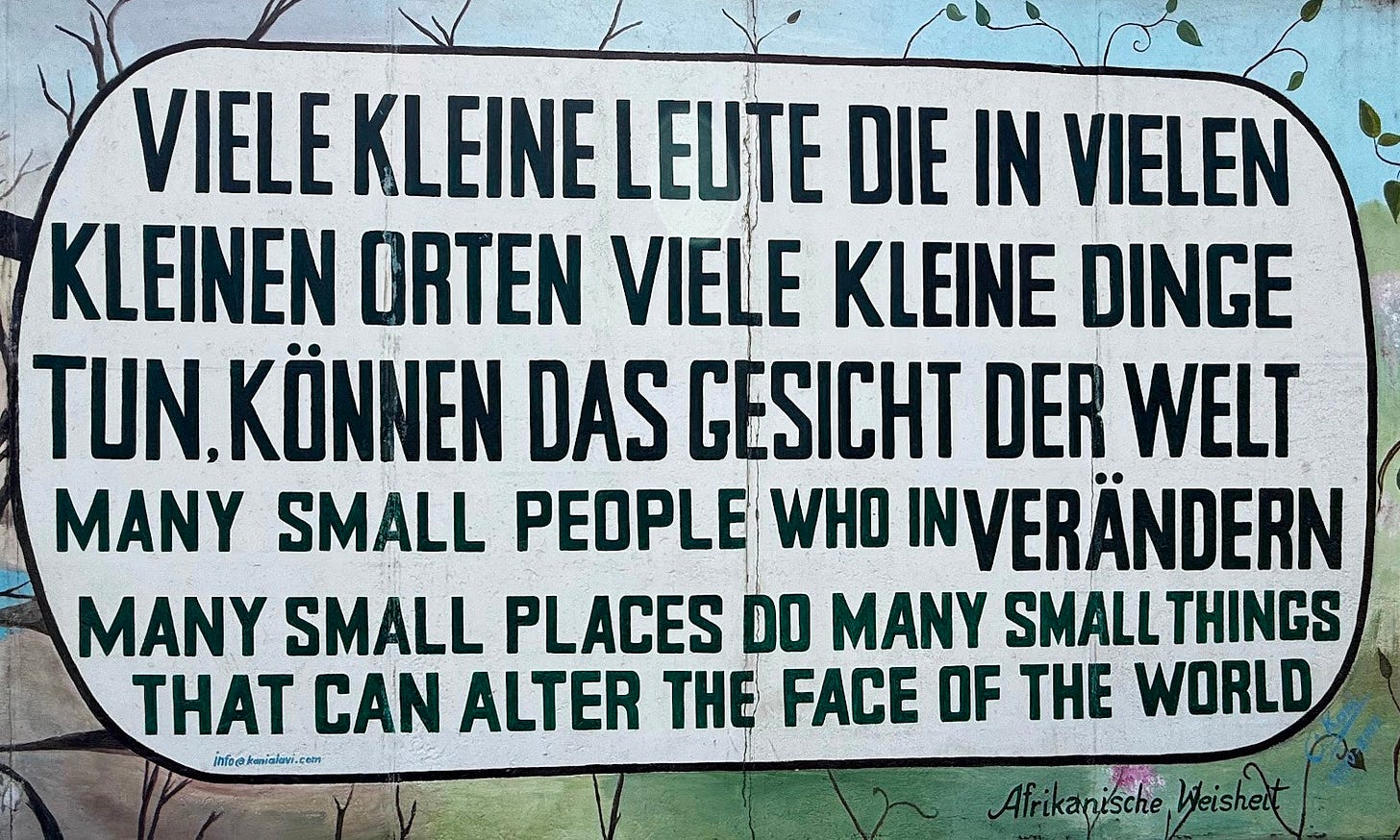

There’s also a literal reminder in Berlin for those of us in the U.S. who have had our hopes dashed in the nascent days of the second Trump term. It’s painted on what remains of the Berlin Wall — now an outdoor gallery for public artwork and another example of Germany’s turning swords into plowshares:

I wish more Americans could grasp that reckoning with our past is not a weakness, but a strength. Thank you for the hopeful reminder that oppressive systems can collapse under their own weight, and that facing hard truths is how a nation moves forward, not backward.